Reading Imaging

In the ICU, the most common imaging modalities you will see utilized that we directly read are:

Chest X-Ray

CT chest (CT angiogram)

Cardiac echo

You will see other types of studies done (CT A/P, doppler US venous legs, CT head, KUB) that we don’t directly read as often. Each hospital has a radiologist on call that read these; depending on the hospital, the radiologist may not be available after a certain time of night.

Chest radiograph (CXR)

According to med-line, “a chest radiograph, called a chest X-ray, or chest film, is a projection radiograph of the chest used to diagnose conditions affecting the chest, its contents, and nearby structures”. It can be done PA, AP, or lateral as well as supine or sitting up.

The correct words used to describe a CXR:

Density: interchanged with the word “opacity”. Hyperlucency (brighter, whiter than expected). Suggests the alveoli are filled with something

Lucency: opposite of density; hypolucency. Suggests air (darker, blacker than expected)

Consolidation: a description of the solidification of lung parenchyma because of airspace pathology - it is not a specific term for infection

When describing a consolidation, you need to know where it is happening

patchy consolidation (like it sounds - patchy)

focal consolidation (one area)

diffuse consolidation (all over)

In order to know whether a CXR is good quality you can use the pneumonic PIER:

Position - supine AP? PA? Lateral?

Inspiration - count the posterior ribs; you should see 10-11 with a good inspiratory effort (green markings)

Exposure - Good lung detail and an outline of the spinal column (red markings)

Rotation - the space between the medial clavicle and the spinous processes should be equal to each other (seen in blue)

This is the same CXR as above. You see at least 10 ribs (marked in green); you can see the detail of the spinal column (marked in red); and when comparing the distance between the spinous processes and the medial clavicle, it is roughly the same on each side (marked in blue).

common things we see

Infiltrates

“As you breathe in, air first enters your trachea (windpipe) and then branches out into progressively smaller airways until it reaches the end: microscopic bubbles called alveoli, where the exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide occurs. When these alveoli fill up with fluid of some kind, it manifests on a chest X-ray as consolidation.

Five main categories of fluid can cause consolidation: blood, water (e.g. pulmonary edema), pus (e.g. pneumonia), cells (e.g. cancer), or protein (certain rare lung conditions). Consolidation shows up in the lungs as a density whose appearance has been compared to fluffy clouds.” (credit: neighborhood radiologist)

SUPPORT DEVICES: None. HEART: Borderline-enlarged but accentuated by the AP projection. LUNGS: Bilateral multifocal infiltrates are again noted. Progression For technique is noted. PLEURAL SPACE: Unremarkable. BONY STRUCTURES: Unremarkable. AORTA: unremarkable. MEDIASTINUM: Normal..

IMPRESSION:

There are bilateral multifocal infiltrates that have shown slight progression even allowing for technique. Pneumonia should be excluded.

Single AP view of the chest. Patient is rotated to the right. Multiple cardiac leads and wires overlie the chest. There is marked cardiomegaly. There are persistent diffuse alveolar and interstitial infiltrates which have worsened since prior examination. The right CP angle is cut off. I do not see definite evidence of effusion or pneumothorax. The bony structures reveal osteopenia. There are stents overlying the left subclavian and axillary soft tissues as well as evidence of left upper extremity dialysis access.

IMPRESSION:

Cardiomegaly; Worsening bilateral alveolar and interstitial infiltrates consistent with bilateral pneumonia.

pleural Effusions

“A pleural effusion means fluid accumulation in the pleural cavity, a potential space that is located between the lungs and the rib cage. “Potential space” is not a new home flipping show; it means a space that is normally empty but has the potential (aah, get it?) to be filled with something, like the inside of an uninflated balloon.

The pleural cavity is sandwiched between two thin membranes called the pleura, one of which covers the outside of the lungs and the other the inside of the rib cage. Normally the pleural cavity contains a minuscule amount of fluid for lubrication purposes, but under certain conditions it can fill with fluid and create a pleural effusion. If it is large enough, one can see a horizontal line representing the top of the fluid collection with slight sloping up on each side, a characteristic shape called a meniscus.

Pleural effusion is a common cause of atelectasis in the adjacent lung. Many different types of conditions can cause pleural effusions, with heart failure and pneumonia among the more common ones. (A chest X-ray example of pleural effusion can be seen above under silhouette sign)” (credit: neighborhood radiologist)

SUPPORT DEVICES: A left thoracotomy tube remains in place. HEART: Difficult to evaluate but possibly not enlarged. LUNGS: There are bilateral infiltrates. Basilar changes may represent pneumonia or atelectasis. PLEURAL SPACE: Effusions are felt to be present.. BONY STRUCTURES: Unremarkable. AORTA: unremarkable. MEDIASTINUM: Normal..

IMPRESSION:

There are bilateral effusions. Effusion the right may be layering creating the density in the right lung. There are bilateral infiltrates. Basilar changes may represent pneumonia or atelectasis.

SUPPORT DEVICES: Left jugular central line terminates in the region of the SVC. Small bore chest tube overlies left hemithorax. HEART: Prominent but difficult to evaluate. LUNGS: The left pleural effusion is been largely drained. There is residual density at the left base. There is a shallow inspiration. There is a patchy area of basilar atelectasis on the right. PLEURAL SPACE: Residual effusion is felt to be present. There is no pneumothorax.. BONY STRUCTURES: Unremarkable. AORTA: unremarkable. MEDIASTINUM: Normal..

IMPRESSION:

Small bore chest tube is been introduced. Much of the left pleural effusion is been evacuated with residual noted in the left base. There is probably consolidation the left base. There is right basilar atelectasis. There is no pneumothorax.

Line placement

After your place your lines, you will often need to approve the Chest X-ray for the nurse to use it. The tip of your line, no matter where you insert, should be at the SVC or the cavo-atrial junction (level of the 1st ICS above the carina).

When you place a central line it should be:

R sided IJ: oriented vertically with its tip over the anatomical location of the SVC (1.5 cm above level of carina)

L sided IJ: goes down, courses from the IJ to the subclavian vein to the SVC. Like a backwards “S”

Right sided CVL (red arrows) without pneumothorax

A patient with two central lines; on on the right side (blue arrows) and one on the left side (red arrows). Note with the left sided line it is the backwards “s”

Often, catheters can be misplaced in the vein. Most commonly there are a couple situations we run into:

Brachiocephalic Placement: They can be in the innominate vein/brachiocephalic vein which is formed from the union of each corresponding internal jugular vein and subclavian vein

Azygous placement: They can be in the azygous vein, a unilateral vessel that ascends in the thorax to the right side of the vertebral column, carrying deoxygenated blood from the posterior chest and abdominal walls. The tip is seen abruptly looping upward and posteriorly in the right superior mediastinum. Most likely to occur from left sided approach

Tip is Horizontal: most common on L sided catheters, may cause vessel erosion if positioned long term

The tip of this catheter is in the brachiocephalic vein rather than the SVC

R internal jugular CVL in the Azygous vein

Horizontal Tip

Arterial Misplacement

In general the most important thing when it comes to line placement is to know its not arterial. This can happen, but as long as you do not use the line that is the most important thing. Anything infused in a carotid central line will go straight to the brain and can result in permanent brain damage, strokes, etc. Often an arterial placed central line will warrant a CT chest and cardio-thoracic surgery consult, especially if the line is a vascath.

Central line in artery; notice on RIJ CVL crosses midline to the right of the carina (instead of the left)

Central line in artery

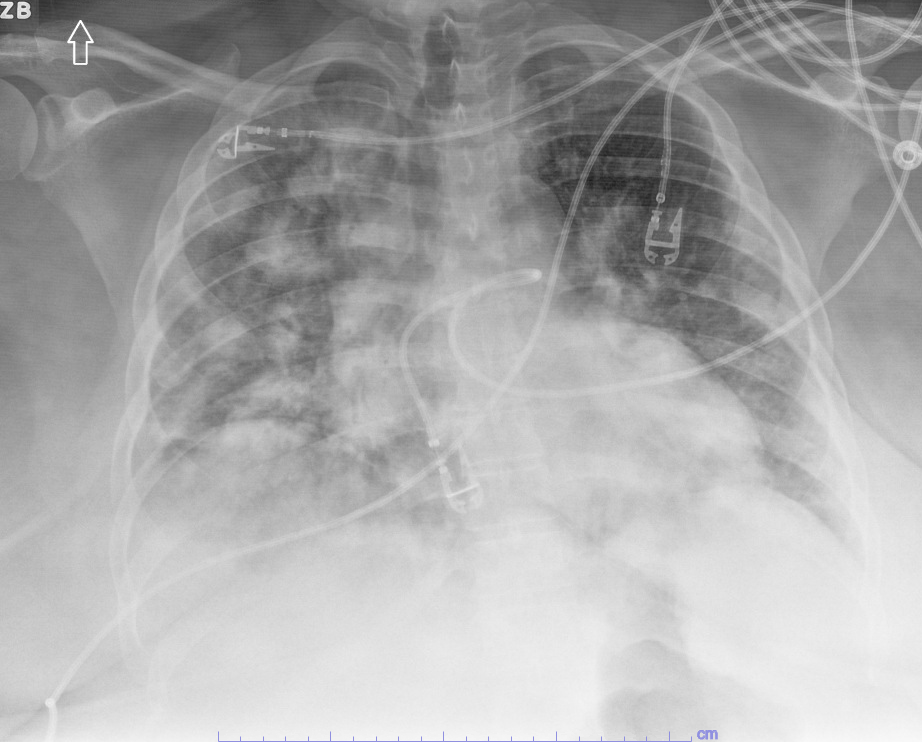

Looking for Pneumothorax (PTX)

One of the primary reasons we always get a chest x-ray after placing a central line is to a) confirm line placement and b) ensure we don’t cause a pneumothorax. Pneumo (air) thorax (chest), or “collapsed lung”, is the entry of air in the pleural space either spontaneously or as a result of trauma/tears. We will sometimes see this with positive pressure ventilation (air is being pushed into lung -> barotrauma) but we can also see it from our line placement. If you put your needle to deep you can damage the pleura and introduce air. It’s especially risky when placing subclavian lines.

Air on x-ray is going to be black, while fluid/anything dense is going to appear more white. Often the rib lines and be confused for a PTX; its important to zoom in and look for lung markings. See an example of a pneumothorax found on a chest x-ray below; both are the same image, one has the PTX clearly marked while the left does not.

Sometimes, these changes can be subtle; sometimes they’re much more pronounced. If after placing your line, a patient begans to become hypoxic and hypotensive, think tension (traumatic) pneumothorax. To rule this out you will listen to lung sounds (absent in tension pneumothroax), order a chest x-ray, and you can use ultrasound to look for a lines, b lines and lung sliding (absent in tension pneumothorax; ask your veteran APP to show you this).

1a) Unmarked CXR; click the image to view closer

1b) Same CXR as to the left; but with pneumothorax marked; click the image to view closer

2a) Patient above after bilateral chest tubes placed; unmarked image. Same as the image to the right. These chest tubes are called “pig tail” catheters because they appear to look like literal pig tails; they’re placed similar to CVLs. Click the image to get closer view

2b) Patient above after bilateral chest tubes placed; image w/bilateral PTX marked. Same as the image to the left. You can see the PTX on the patients left (your right) is quite large and obvious, while the PTX on the patients right (your left) is much more subtle.Click the image to get closer views

3) The same patients lungs once large bore chest tubes were placed bilaterally by interventional pulmonology; small residual PTX on the patients right (your left) but large pneumothorax on the patients left (your right) has resolved. Click image to get closer view